Historians respond to John F. Kelly’s Civil War remarks: ‘Strange,’ ‘sad,’ ‘wrong’

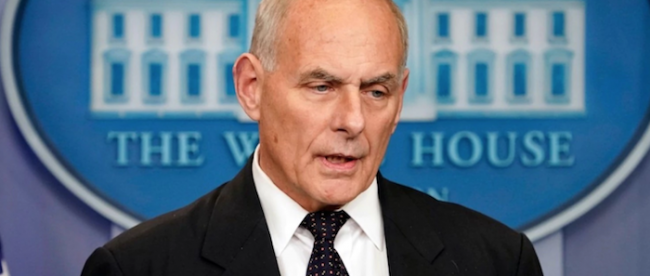

White House Chief of Staff John F. Kelly was the guest for the premiere of Laura Ingraham’s new show on Fox News Monday night. During the interview, he outlined a view of the history of the Civil War that historians described as “strange,” “highly provocative,” “dangerous” and “kind of depressing.”

Kelly was asked about the decision of a church in Alexandria to remove plaques honoring George Washington and Robert E. Lee.

“I would tell you that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man,” Kelly said. “He was a man that gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was always loyalty to state first back in those days. Now it’s different today. But the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War, and men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had them make their stand.”

“That statement could have been given by [former Confederate general] Jubal Early in 1880,” said Stephanie McCurry, professor of history at Columbia University and author of “Confederate Reckoning: Politics and Power in the Civil War South.”

“What’s so strange about this statement is how closely it tracks or resembles the view of the Civil War that the South had finally got the nation to embrace by the early 20th century,” she said. “It’s the Jim Crow version of the causes of the Civil War. I mean, it tracks all of the major talking points of this pro-Confederate view of the Civil War.”

Kelly makes several points. That Lee was honorable. That fighting for state was more important than fighting for country. That a lack of compromise led to the war. That good people on both sides were fighting for conscientious reasons. Both McCurry and David Blight, professor of history at Yale University and author of “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory,” broadly reject all of these arguments.

“This is profound ignorance, that’s what one has to say first, at least of pretty basic things about the American historical narrative,” Blight said. “I mean, it’s one thing to hear it from Trump who, let’s be honest, just really doesn’t know any history and has demonstrated it over and over and over. But Gen. Kelly has a long history in the American military.”

Blight described Kelly’s argument in similar terms as McCurry — an “old reconciliationist narrative” about the Civil War that, in the last half-century or so has “just been exploded” by historical research since.

The idea that compromise might have been possible was rejected out of hand by both McCurry and Blight.

“It was not about slavery, it was about honorable men fighting for honorable causes?” McCurry said. “Well, what was the cause? . . . In 1861, they were very clear on what the causes of the war were. The reason there was no compromise possible was that people in the country could not agree over the wisdom of the continued and expanding enslavement of millions of African Americans.”

There were a number of compromises on slavery that led up to the Civil War, from the drafting of the Constitution to the addition of new states to the Union.

“Any serious person who knows anything about this,” Blight said, “can look at the late 1850s and then the secession crisis and know that they tried all kinds of compromise measures during the secession winter, and nothing worked. Nothing was viable.”

“All of these compromises were about creating a division where slavery already existed and where for a time they conceded that the Constitution shackled them in their ability to attack it,” McCurry said. Before the war, the strategy for dealing with slavery was to contain it. By 1860, she said, the North’s economic success and expanding population and the South’s loss of representation in national politics put slavery at risk. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 allowed Southern slaveholders — who had $4 billion in wealth in the form of enslaved people, McCurry said — to argue that the threat to slavery was imminent.

“In 1861, compromise wasn’t possible because some Southerners just wanted out. They wanted a separate nation where they could protect slavery into the indefinite future,” McCurry said. “That’s what they said when they seceded. That’s what they said in their constitution when they wrote one.”

Kelly’s framework is “also rooted, frankly, in a Lost Cause mentality that swept over American culture in the wake of the war, swept over Northerners,” Blight said, “this idea that good and honorable men of the South were pushed aside and exploited by the ‘fanatical’ — ironically — first Republican Party.”

Blight noted that Lee wasn’t simply defending his home state of Virginia against Northern aggression.

“Of course we yearn for compromise, we yearn for civility, we yearn for some common ground,” he added. “But, look, Robert E. Lee was not a compromiser. He chose treason.”

“The best of the Lee biographies show that Lee was a Confederate nationalist,” Blight said. “He knew what he was fighting for.”

Both historians, though, held particular disdain for the idea that putting state over nation was the essence of the fight.

“My God, where does he get that from?” Blight asked. “That denies the very reason to be, the essential reason for the existence of the original Republican Party, which formed in the 1850s to stop the expansion of slavery and ended up developing a political ideology that threatened the South because they really were going to cordon off slavery.”

“This idea that state came first? No, it didn’t!” he said. “The Northern people rallied around stopping secession! This comment is so patently wrong.”

“It’s one thing to say Lee chose state over country,” McCurry said. “What [Kelly] says is that washis country. That would be news to 350,000 Union war dead.”

“It’s just so absurd,” Blight said. “It’s just so sad. It’s just so disappointing that generations of history have been written to explode all of this and yet millions of people — serious people; experienced, serious people and now people with tremendous power — have grown up believing all this.”

There was, however, a small silver lining.

“This Trump-era ignorance and misuse of history is forcing historians — and I think this is a good thing — to use words like ‘truth’ and ‘right or wrong,’ ” Blight said. “In the academy we get very caught up in relativism and whether we can be objective and so on, and that’s a real argument.”

“But there are some things that are just not true,” he said. “And we’ve got to point that out.”